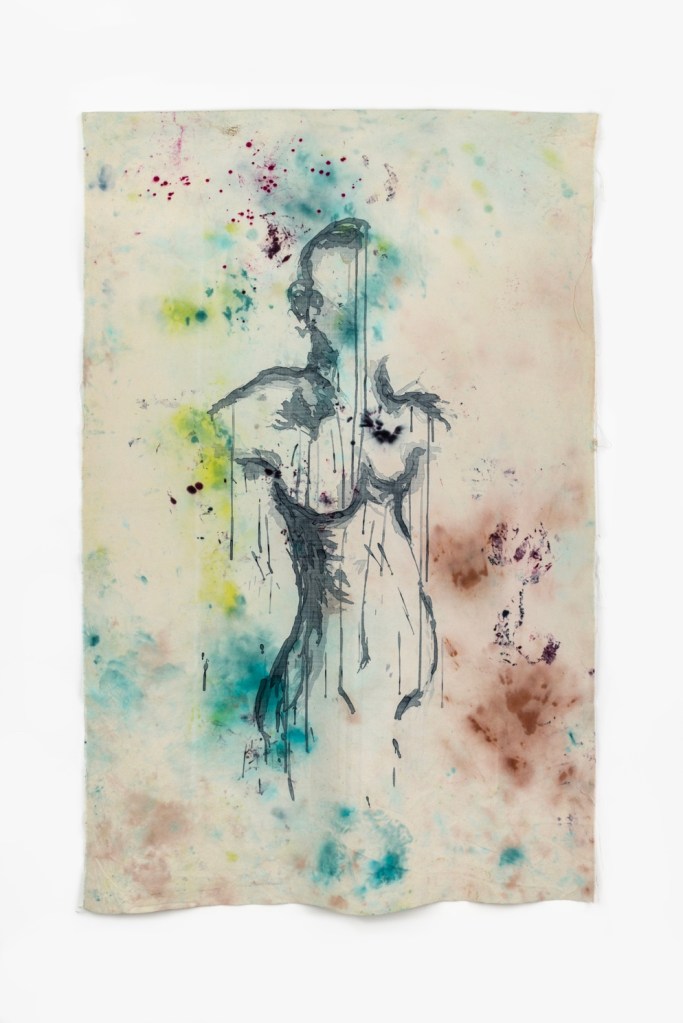

In 2009, a shocking, unexpected event happened. My husband Carl, the father of our sons, ended his life through suicide. It was a cataclysmic event that changed our lives forever. In 2023, another unexpected event happened. The piece of work below was created by chance; it happened because I was trying to find my voice whilst studying at the Royal College of Art (RCA).

2023 Silk screen, mono-print on cotton print-room backing cloth, procion dyes.

101 x 62cm

Surviving loss through suicide is challenging – it changes who you are and how you see the world. Once I may have considered this piece of work a by-product of my endeavour to make a precise mono-print on pristine white cotton organdie; today I see it as an accumulation of events and happenings, and their effects on my being and living.

Traumatic loss is unimaginable and unspeakable. It is difficult to define and difficult to represent. The memories of what happened fragment and bury themselves deep in the mind, lying there silently, ready to pounce at any inopportune moment. To live, the fight or flight mode needs to be disengaged, the thoughts unravelled, and the hurt spoken about. But this is hard to do without a suitable safe space and the right support. Surpassing all expectation, the Royal College of Art filled this role. My need to talk was nurtured by my peers and encouraged by my tutors. This did not mean that the sadness of the situation would give me an easy ride through the college, but it did provide fuel for my fire when I was challenged, and provoked thoughtful conversations when shared with my peers.

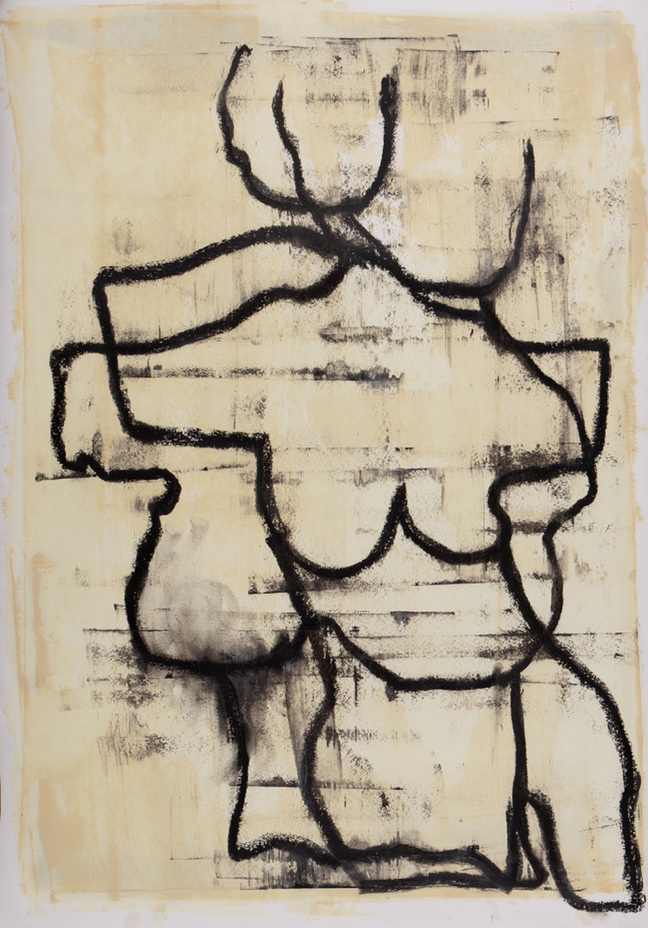

The challenges started as soon as the course began. In Unit one I was asked about my use of drawing – why did I only draw with my sewing machine and what happened before I started the work? I knew the answer, I was daunted by my preconceived idea of what drawing with pencil and paper should be. I considered the conversation; I was anxious about failing, and scared of drawing, but I knew that the question was valid. The stakes were high, I wanted to grow as an artist and I knew that this course would help me to do that. Tentatively, I picked up a piece of charcoal and found some paper. With contemplative touch, I eyes closed and felt the tension reverberating through my body. As the charcoal hit the paper, I made marks that responded to what my hand touched rather than what my eyes thought they could see. As my emotional state altered, the marks changed in response. The new drawings were raw and the subject matter personal. I understood that the spontaneous and uncontrolled marks represented more than line and form alone – they embodied how I felt inside. A line of enquiry had been opened.

Julie Heaton blind touch drawings on A1 cartridge paper.

Charcoal and oil pigment, sizes 59 x 84cm

For the first year, the drawings were made on paper with a variety of mark making methods, however, I was curious about how fabric could be included in the process. I was intrinsically drawn to fabric; I had stitched as a child, influenced by my mum, who made many of our clothes by copying designs that she saw in catalogues. We wrap ourselves in fabric when searching for comfort and warmth or when we need to impress for a significant date. It is akin to skin and the movement of the human form. Fortunately, the RCA has a cornucopia of opportunities. At the start of year two I tried a silk screen, mono-print master-class – the medium was liberating. I knew nothing about the process and so I could make without any rules. It was unpredictable and transformative; it became all consuming. I could continue my line of enquiry. With my eyes closed, I dipped one hand in the pot of dye and traced my inner thoughts onto the silk-screen. The lines were uncertain, the marks often messy. They could be layered, as are the complexities of thoughts and experiences, each one affecting the next, as it does in life. I would have one attempt to print the drawing onto the fabric. Sometimes it would go wrong, but at other times I would be left with ethereal marks that spoke about the fragility of being human. I could layer the mono-prints, alter the scale and placement, work on pristine white fabrics or heavily stained, reclaimed backing cloths. The possibilities were endless.

Julie Heaton work in progress, the textiles print room, RCA

Throughout this new and experimental way of working I was continually questioned about my research and my rationale. New artists were recommended to challenge and support my thinking. I quantified my process with continual references to the wide-ranging research presented in my dissertation. From authors to visual artists, I found inspiration in others who needed to make work that responded to traumatic loss. Primo Levi1, Scolastique Mukansonga2 and Yiyun Li3, authors who wrote about personal traumatic loss on both an immeasurable and intimate scale. Artists such as Ana Mendieta4 and Rozanne Hawksley5 who poured their own immeasurable heartache into work that endeavoured to talk about displacement and isolation. The impact of the research was phenomenal, it guided me through an intimate period of discourse, one where I was trying to discover how talking about the unspeakable can happen cathartically. At no time did I expect it to provide a resolution, it was the need of a safe space that it could offer, where my voice could be nurtured rather than silenced.6

My endeavours to find my voice meant that I spent many hours in the print room on floor 5 learning how to be a printer. I was acutely aware of the messes that I was making and the patience of the technical team as they answered my innumerable questions. However hard I tried, I always gathered unwanted splashes and drips. Then the accident happened. Whilst trying to make a delicate print on lightweight cotton organdy, the excess dye from the monoprint flooded onto my messy backing cloth. I immediately understood what I had – all the messes and stains that we gather in life, the ones that affect the decisions that we make and the words that we say. It felt like a lightbulb moment, but could I replicate this process that had happened by chance?

With so many considerations, the issue was discussed at tutorials and in crits. The work of Jacqui Hallum was recommended as a source of inspiration. Encouraged by her painted fabrics, altered and affected by the uncontrollable environmental elements, I decided to mix up coloured dyes that I wouldn’t particularly choose. I put them into leaky bottles, wrapped them in my printing cloths and carried them around in my backpack. The colours bled into my fabrics with a pattern of haphazardness. I took them back to college and transposed my mono-prints onto the randomly stained backing fabrics. The process was beyond any control and the outcomes certainly unknown. They were a result of activity that was not planned, and the conversations were empowering. The titles of the work came easily; thoughtful but provocative. A conversation was open, and a vulnerability was shared with my tutors and my peers.

Silk screen, mono-print on cotton canvas, procion dyes, size 175 x124cm

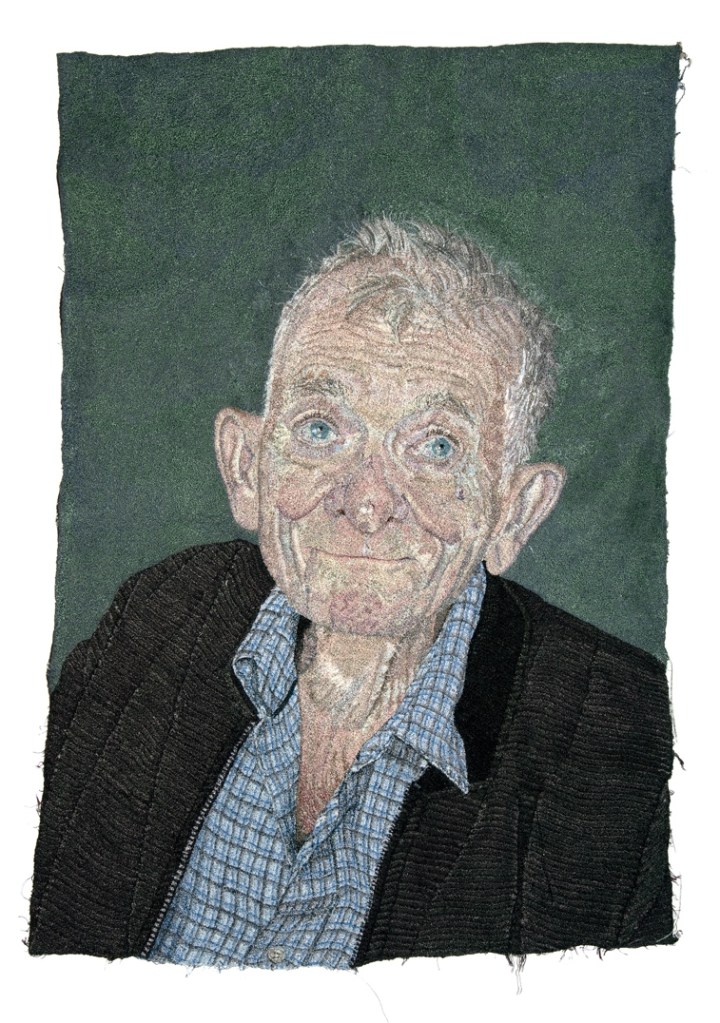

The work was experimental, they happened because I was challenged to move outside of my comfort zone, a change from my established practice. I knew that my stitched drawings that I created before coming to the RCA were executed at a highly technical level. I could measure that by the accuracy of the mark making. I could not do that with the body of work that I had produced at the RCA. It was a visceral embodiment of an emotional torment endured following traumatic loss. It was personal, but through the making I had opened a conversation that could benefit my sense of being and allow others to join the conversation if they felt able. But I also had to accept that some people might easily pass it by.

Free machine embroidery, size: 40 x 57cm

Made before I started at the RCA

Going to the Royal College of Art had been an exciting but daunting prospect. I had wondered how it would affect my practice, and if it might empower my voice as an artist. The outcome exceeded all my expectations. I had made new and wonderful friends, and had challenging, but critically engaging conversations with my tutors and peers. I achieved a distinction in my dissertation and found solace in what I learnt whilst researching. But perhaps the greatest achievement, the ability to give substance to a conversation that had been obscured by an irrational fear of saying how it really is to lose a loved one through suicide.

A special thank you to my tutors, Dr Fiona Curran and Celia Pym.

Julie Heaton ‘I carry the story but hold on to the dreams’ 2023

Silk-screen, mono-print on cotton canvas, procion dyes, size: 135 x 87cm

Please do come and see pieces of the work that I produced at The Royal College as part of seam collective’s exhibition tour, A Visible THREAD. I will be experimenting with different hangings as the tour moves from one gallery space to the next. Currently ‘If only we had known some different words’ is on show at Black Swan Arts, Frome; ending 29 October 2023.

The tour continues to:

- The Wirth Gallery, Sherborne Girls School, Sherborne: 6 – 27 January 2024

- Llantarnam Grange, Cwmbran: 17 February – 4 May 2024

- Thelma Hulbert, Honiton: 20 July – 31 August 2024

See seam collective’s website and Instagram for full details of the tour, workshops and participatory events and sign up for seam’s newsletter for regular news and updates.

Check my RCA website for more images of the work made on my MA The Royal College of Art You can see my free machine embroidered drawings at Julieheaton.com and discover what I am up to now @julieheatonartist on Instagram.

And my exciting news, I will be starting free machine embroidery workshops in the New Year. Please DM me via Instagram if you are interested.

Julie Heaton

- Primo Levi: An assuming chemist who survives the atrocities of the Holocaust speaks of the horrors with a compassionate voice for sake of humanity.

- Scolastique Mukasonga: Survivor and author of her family’s brutal entanglement with the Tutsi genocide of the 1994 in Hutu-controlled Rwanda.

- Yiyun Li: A mother devasted by the death of her son through suicide engages with the conversations that she longs for but cannot have.

- Ana Mendieta: Cuban artist traumatised by her forced departure from her homeland.

- Rozanne Hawksley: Conceptual visual artists whose work reflected subjects of war, loss, grief and remembrance.

- Following loss through suicide, it can be difficult to talk because of the shame and stigma that surrounds the death. Without a conversation, the cycle of loss through generations cannot be broken.

SELECT REFERENCES:

- Levi, Primo, If This is a Man: The Truce (Great Britain: Abacus, 1987).

- Li, Yiyun, Where Reasons End (Great Britain, Penguin Books, 2019).

- Mukasonga, Scolastique, Cockroaches (New York: Acrchipelago Books, 2020).

- Van Der Kolk, Bessel, The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, brain and body in the transformation of trauma (United Kingdom: Penguin Books, 2015).

- Wertheimer, Alison, A Special scar: The Experiences of People Bereaved by Suicide (London and New York: Routledge, 2008).